🌊 Rays of Southeast Asia

🤿 The Ocean’s Most Misunderstood Giants — and Why They’re More Vulnerable Than You Think

Rays are often treated as a supporting act in diving. When they appear, it’s usually in passing — a manta gliding overhead at a cleaning station, a stingray lifting silently from the sand — before attention shifts back to sharks, turtles, or the reef itself.

Yet rays are not sharks with wings, nor are they passive background animals. They are highly specialised, evolutionarily distinct species with slow life cycles, complex behaviours, and ecological roles that make them especially vulnerable to human pressure — particularly in Southeast Asia.

A Giant, Oceanic Manta Ray

🧠 Slow to mature

🐣 Few offspring

📍 Strong site fidelity

🌏 Heavy overlap with fishing and tourism

Some rays are instantly recognisable and deeply loved. Manta and mobula rays are bucket-list sightings, photographed endlessly and celebrated widely. Others are cryptic, easily missed, or only briefly glimpsed — eagle rays crossing a channel, stingrays half-buried in sand, quietly going about their lives beneath the notice of most divers.

Many of these less visible species face intense pressure from fishing, bycatch, habitat disturbance, and cumulative stress — often without the legal protections or conservation attention afforded to more charismatic marine animals. Declines tend to be gradual and quiet, making them easy to overlook until sightings become rare.

Understanding rays means understanding why their populations struggle to recover, even when pressure is reduced. It also means recognising why diver behaviour — how close we approach, how we control buoyancy, how we move through sandy and reef environments — plays a larger role than most people realise.

In Southeast Asia, rays offer a different kind of lesson from sharks or turtles. They remind us that vulnerability in the ocean is not always dramatic. Sometimes it’s subtle, slow, and unfolding just beneath the surface.

Rays belong to the same ancient group as sharks, known as elasmobranchs. Like sharks, they have skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone, rely on highly developed senses to interpret their environment, and tend to live slow, low-reproduction lives that make populations vulnerable to pressure.

🦈 Cartilage skeletons

⚡ Electroreception to detect prey

🐣 Slow growth and low reproductive rates

These shared traits are part of why rays and sharks face similar conservation challenges — but rays differ in ways that are easy to overlook.

What truly sets rays apart is their body plan. Their flattened shape and greatly enlarged pectoral fins allow them to move through the water in a way that looks almost like flight. Some species cruise gracefully through the water column, while others spend much of their time resting directly on the seabed.

Unlike sharks, most rays have their gills positioned on the underside of the body. To avoid inhaling sand, many use openings called spiracles behind the eyes to draw in water while resting. This anatomy allows rays to exploit habitats sharks cannot — particularly sandy bottoms, lagoons, and reef edges.

🪽 Enlarged pectoral fins for propulsion

🌊 Ventral gills adapted for bottom-dwelling

🏝️ Strong association with sand and sediment

Just as important, “ray” is not a single type of animal. It’s a broad category that includes a wide range of lifestyles and ecological roles. Giant pelagic manta rays feed by filtering plankton in open water. Eagle rays hunt mobile prey over reefs and channels. Stingrays and whiprays specialise in locating animals hidden beneath sand using electroreception.

This diversity is one of the main reasons rays are often misunderstood. They don’t behave like a single group, face the same threats, or respond to pressure in the same way. Some are highly visible and celebrated. Others are cryptic, easily disturbed, and rarely noticed until they’re gone.

Understanding rays starts with recognising this variety — because protecting them requires acknowledging that there is no single “ray story,” only a shared vulnerability shaped by slow life histories and close overlap with human activity.

🤿 The Rays Divers Commonly See in Southeast Asia

🐋 Manta and Mobula Rays

Manta and mobula rays are the most iconic rays in Southeast Asia, and for many divers they represent a highlight of an entire trip. They’re most often encountered at cleaning stations, where reef fish remove parasites, or cruising through channels and current-swept areas between reefs.

These rays are intelligent, slow-moving, and long-lived. They return repeatedly to the same sites, which makes them both predictable for divers and especially vulnerable to disturbance. Their slow reproduction means populations recover very slowly once numbers decline — even when pressure is reduced.

Although they’re often grouped together in conversation, mantas and mobulas are not the same, and understanding the difference helps explain both their behaviour and their vulnerability.

🐋 Manta Rays: The Largest and Most Familiar

A Manta Rays glides past gracefully

Manta rays are the largest rays most divers will ever encounter, and Southeast Asia remains one of the best regions in the world to see them reliably. Warm waters, strong currents, and predictable plankton blooms create the conditions mantas depend on — and the conditions that draw divers year after year.

Divers in Southeast Asia may encounter two types of manta rays: reef mantas and oceanic mantas.

🌊 Reef manta rays are by far the most commonly seen. They tend to stay relatively close to coastlines and reefs, returning repeatedly to the same cleaning stations where reef fish remove parasites. This strong site fidelity is why manta encounters are so reliable in places like Komodo National Park, Raja Ampat, and parts of the Philippines — and also why those sites are especially vulnerable to crowding and repeated disturbance.

🐋 Oceanic manta rays are generally larger and far more wide-ranging. They spend much of their lives offshore and in deeper water, occasionally passing through channels or visiting cleaning stations when conditions are right. Encounters with oceanic mantas are less predictable, often brief, and usually associated with strong currents or open-ocean influence rather than fixed reef sites.

In Southeast Asia, oceanic manta sightings are most often reported in exposed, current-driven regions and along deep-water drop-offs, including parts of Komodo National Park, offshore sites in Raja Ampat, and remote areas of the Philippines such as Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park. These encounters often happen away from established cleaning stations, when plankton concentrations or currents draw mantas closer to reefs.

Because oceanic mantas are not tied to the same predictable sites as reef mantas, divers may only see them fleetingly — a single pass through a channel or a brief appearance at depth — making each sighting especially memorable, but also harder to manage and study.

Despite these differences in behaviour and habitat use, both manta types share the same underlying vulnerability. They grow slowly, live long lives, produce very few offspring, and depend on specific aggregation sites to feed and clean effectively. Because of this, even small increases in mortality or repeated disturbance can have long-lasting effects on local populations.

For divers, the calm presence of a manta can feel effortless and timeless. In reality, each encounter is taking place within a life history that leaves very little margin for error.

🐟 Mobula Rays: Often Seen, Rarely Understood

🐟 Mobula rays are closely related to mantas but are typically smaller and more numerous. They’re sometimes called “devil rays” — a misleading name that has contributed more to misunderstanding than protection. In the water, mobulas feel very different from mantas: faster, more directional, and far less likely to linger.

Rather than circling cleaning stations, mobulas are more often encountered moving quickly through the water column, crossing channels or reef edges, or schooling in open water. Encounters tend to be brief — a group passing at speed, or a sudden appearance at the edge of visibility — before they vanish just as quickly.

In Southeast Asia, mobula sightings are frequently reported in current-influenced areas and along offshore reef systems. I’ve personally encountered mobula rays around Pulau Tenggol in Malaysia, where strong currents and open-water conditions create ideal habitat for fast-moving pelagic species. Similar sightings also occur sporadically in parts of Indonesia and the Philippines, often away from the most heavily dived sites.

Because mobulas don’t linger and often appear without warning, many divers mistake them for juvenile mantas — or don’t realise what they’ve seen at all. This fleeting nature contributes to how easily mobulas are overlooked, both underwater and in conservation conversations.

Like mantas, mobulas reproduce slowly and are highly vulnerable to fishing pressure and bycatch. In some regions, they are even more heavily targeted than mantas, yet receive far less public attention or protection. Their declines are quieter, harder to track, and easier to miss — until sightings become rare.

🧠 Why These Differences Matter

From a diver’s perspective, mantas and mobulas may feel similar — large, graceful rays moving effortlessly through the water. But their differences influence how they respond to pressure.

🧭 Reef mantas are especially vulnerable to crowding and repeated disturbance at fixed sites.

🌊 Oceanic mantas are vulnerable to fisheries across wide geographic ranges.

🐟 Mobulas are vulnerable to being overlooked entirely, despite often being caught in large numbers.

Understanding which ray you’re seeing — and how it uses the environment — helps explain why responsible diver behaviour matters so much at manta sites, and why conservation attention needs to extend beyond the most famous animals.

For divers, these encounters are unforgettable. For the rays, they are moments within a life shaped by slow growth, limited reproduction, and increasing overlap with human activity.

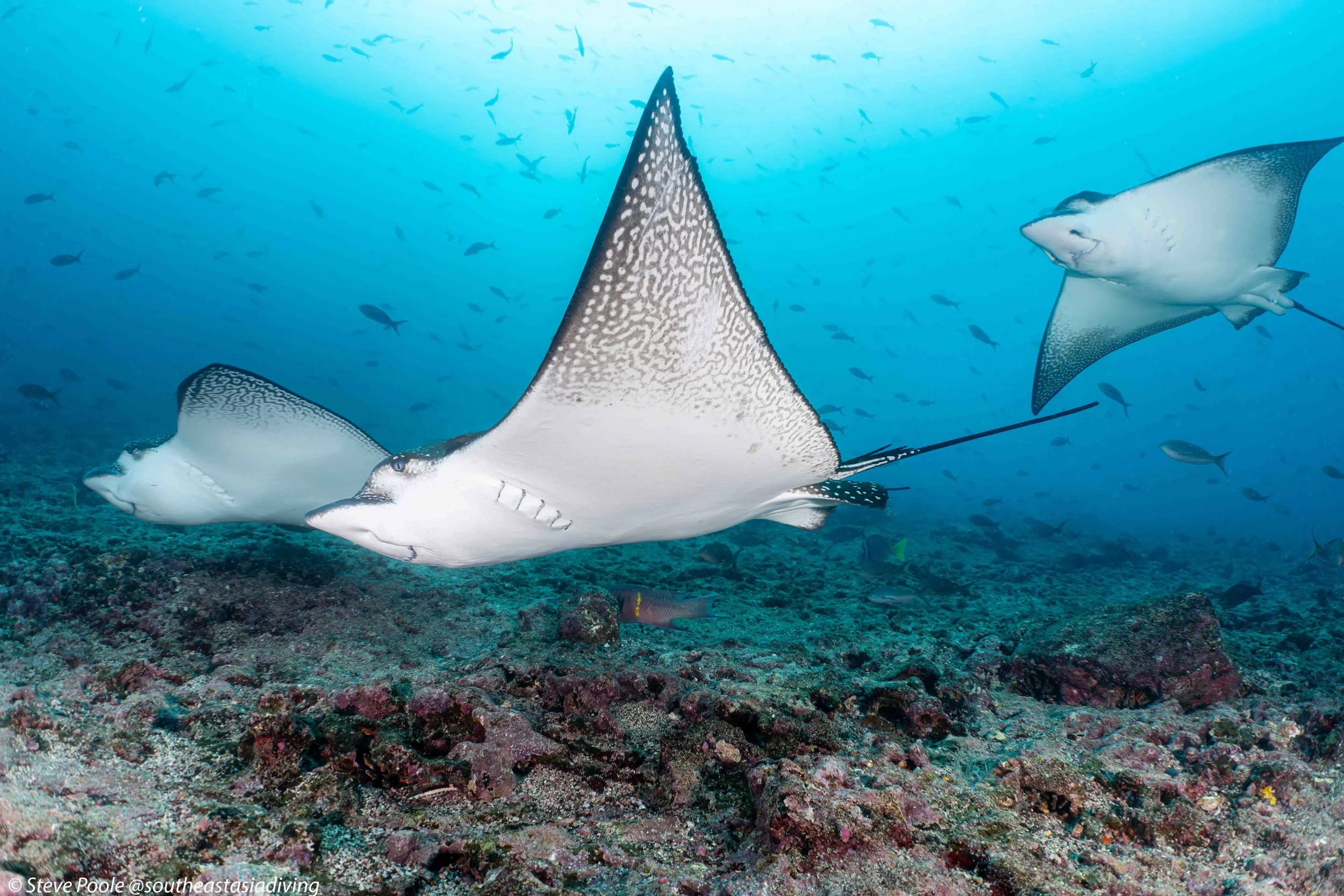

🦅 Eagle Rays

The Fast Movers That Disappear First

Eagle rays are more elusive than mantas or mobulas. They’re most often seen crossing reefs or sandy channels in small groups, moving with speed and purpose rather than lingering in one place. Encounters are usually brief — a silhouette gliding past, a flash of spotted wings — before they disappear into blue water.

Because they favour open channels, reef edges, and current-swept crossings, eagle rays are typically encountered while transiting rather than hovering. I’ve seen them repeatedly at Sipadan and nearby Kapalai, where deep walls and sandy channels funnel pelagic life, as well as in Komodo National Park, particularly in high-flow areas between reefs. These environments suit their fast, purposeful style of movement.

Eagle rays don’t use cleaning stations in the same way mantas do and rarely tolerate close approach. As a result, many divers misidentify them or fail to recognise them at all. It’s common to hear them described simply as “a ray,” even though their behaviour is distinctly different from other species.

Their mobility also makes them highly sensitive to pressure. Eagle rays respond quickly to disturbance, altering routes or abandoning areas that experience repeated boat traffic, fishing activity, or heavy diving. Because of this, they’re often among the first rays to vanish from heavily used sites — long before divers realise anything has changed.

That sensitivity makes eagle rays an important signal species. Seeing them regularly usually indicates that an area still has enough space for wide-ranging animals to move naturally. Their absence, on the other hand, can suggest that pressure has become too concentrated, even if the reef itself still appears healthy.

For divers, eagle rays can feel fleeting and frustrating — blink and they’re gone. But that behaviour is precisely what makes them worth paying attention to. Not all reef decline is dramatic or obvious. Sometimes it’s the quiet disappearance of fast-moving animals that tells the clearest story.

🐠 Stingrays (Including Blue-Spotted and Whiprays)

Misunderstood, Not Dangerous

Stingrays are common across Southeast Asia, particularly on sandy bottoms, in lagoons, and along reef edges. Many species — including blue-spotted stingrays and whiprays — spend much of their time partially or completely buried in sand, with only their eyes and spiracles visible as they rest or wait to ambush prey.

Because of this behaviour, stingrays are often encountered unexpectedly — lifting from the sand as a diver approaches or gliding quietly beneath a hovering group. These encounters can feel sudden, but they’re usually the result of a ray reacting to proximity rather than initiating interaction.

Blue Spotted Stingray in Malaysia

Across Southeast Asia, stingrays are among the most widely encountered rays. I’ve seen blue-spotted stingrays and whiprays regularly around Perhentian Islands, Redang Island, Pulau Tenggol, and Tioman Island, as well as throughout Bali and multiple dive regions in Thailand. Similar sightings are common across many other shallow, reef-adjacent sites in the region — often on dives that don’t feel especially “ray focused” at all.

Despite their prevalence, stingrays are not aggressive animals. They do not hunt, chase, or threaten divers. The vast majority of stingray injuries occur when a ray is accidentally stepped on or cornered and reacts defensively — most often in very shallow water.

This is where public perception often diverges sharply from reality. The death of Steve Irwin is frequently cited in discussions about stingrays, and it understandably left a lasting impression. But it’s important to recognise how unusual that incident was. Stingray fatalities are extraordinarily rare, especially given how many people enter the water in stingray habitat every day.

For divers who maintain distance, neutral buoyancy, and awareness — particularly over sand — stingrays pose virtually no threat. In practice, they are far more affected by diver behaviour than divers are by them.

Why Stingrays Are Actually at Risk from Divers

Ironically, stingrays are far more vulnerable to divers than divers are to stingrays.

Because they rest on sand, stingrays are repeatedly disturbed by fin kicks, sediment clouds, and careless hovering in shallow areas. Rays may flush repeatedly, abandoning feeding or resting sites, or remain buried under constant disturbance.

⚠️ Repeated flushing wastes energy

🌫️ Sediment clouds interfere with feeding

📍 Shallow sites experience constant pressure

Over time, this kind of chronic stress alters behaviour and habitat use — even when no physical contact occurs. In popular dive areas, stingrays may simply stop using the most accessible sandy zones altogether.

How to Dive Safely and Respectfully Around Stingrays

The rules for safe stingray encounters are simple and align closely with reef-safe diving principles.

Maintain neutral buoyancy over sand. Avoid sudden descents or hovering directly above buried rays. Keep fins high and controlled, especially in shallow lagoons and entry areas. If a stingray lifts from the sand, pause and give it space — there is no need to follow.

When stingrays are left undisturbed, they are calm, tolerant neighbours in the underwater world. Their reputation for danger says far more about human misunderstanding than ray behaviour.

Stingrays are quiet reminders that not all fear in the ocean is justified — and that the animals we worry about most are often the ones most affected by our presence.

🌊 Other Rays Worth Noticing

The Ones Divers Often Overlook

Beyond mantas, mobulas, eagle rays, and the more familiar stingrays, Southeast Asia is home to a wide range of lesser-known ray species. Depending on location and habitat, divers may encounter cowtail rays, ribbed stingrays, maskrays, whiptail rays, and other species that rarely draw attention — even when they’re right in front of us.

These rays tend to share a few traits: they’re cryptic, bottom-associated, and easy to miss unless you’re actively looking for them. Many rest motionless on sand or blend seamlessly into mixed reef and sediment environments, relying on camouflage rather than movement for protection.

🫥 Excellent camouflage

🏝️ Strong association with sandy and lagoon habitats

👣 Often mistaken for “just another stingray”

Because they lack the size or spectacle of mantas, these species are rarely photographed, discussed, or reported. As a result, many are poorly studied, and reliable population data is limited or nonexistent. In conservation terms, this is a serious problem — it’s difficult to protect what isn’t being tracked.

These lesser-known rays are often the most exposed to coastal development, trawling, habitat loss, and repeated disturbance in shallow areas. Their declines don’t make headlines, and there’s rarely a clear moment when they’re recognised as missing. They simply fade from familiar sites.

For divers, noticing these rays — and recognising them as distinct species rather than background wildlife — is an important shift. Paying attention doesn’t require expertise or identification skills. It starts with awareness: seeing rays not just as shapes on the sand, but as individual animals with specific habits and vulnerabilities.

In many ways, these quieter rays tell the most honest story about reef health. They reflect long-term pressure rather than short-term change, and they remind us that conservation isn’t only about protecting the animals we’re excited to see — it’s also about safeguarding the ones we almost miss.

⚠️ Why Rays Are So Vulnerable

Rays share one critical trait with sharks: they live life in the slow lane. Their biology is built for stability, not rapid recovery — and that makes them especially sensitive to sustained pressure.

Most rays:

🐢 Grow slowly

⏳ Take many years to reach maturity

🐣 Produce very few offspring

📍 Rely on specific habitats or repeat the same sites

These traits work well in stable ecosystems, but they become liabilities when pressure increases.

In Southeast Asia, this vulnerability is magnified by intense overlap with human activity. Rays are caught intentionally for meat and gill plates, and unintentionally as bycatch in nets, trawls, and longlines. Because many rays inhabit sandy bottoms, coastal zones, and reef-adjacent areas, they are especially exposed to fishing methods that operate close to shore.

Unlike faster-reproducing fish, rays cannot rebound quickly once numbers drop. Even when fishing pressure is reduced or removed, populations may take decades to recover — if they recover at all. A few lost adults can have outsized consequences when reproduction is slow and offspring are few.

What makes this especially challenging is that decline is rarely obvious. Rays don’t vanish suddenly. There’s no dramatic crash or single moment of absence. Instead, sightings become less frequent. Encounters feel less reliable. A species that was once “sometimes seen” becomes “rare,” then quietly disappears from familiar sites.

For divers, this kind of change is easy to miss. Trips still feel rich. Reefs still look alive. But the loss is real — and by the time it’s recognised, recovery may already be difficult.

Rays remind us that vulnerability in the ocean isn’t always loud or immediate. Sometimes it unfolds slowly, in the space between dives, over years rather than seasons.

🦈 Rays vs Sharks: Why Protection Looks Different

Sharks tend to dominate conservation conversations — and for good reason. They’re highly visible, widely studied, and have become powerful symbols for ocean protection. In many parts of the world, including Southeast Asia, shark protections now exist that would have seemed impossible a few decades ago.

But those protections often do not extend to rays, even though both groups face many of the same pressures.

Rays are generally harder to monitor and less studied than sharks. Many species are cryptic, bottom-associated, or easily misidentified, which makes population assessments difficult. Without reliable data, protections are slower to appear — or never arrive at all.

📉 Fewer population studies

📜 Patchy or absent legal protection

🕸️ High exposure to bycatch

In some fisheries, rays are targeted deliberately for meat or gill plates. In others, they’re caught incidentally in nets, trawls, and longlines with little reporting or oversight. Their flattened bodies and tendency to rest or forage near the seabed make them especially susceptible to fishing methods that operate close to shore — exactly where human activity is most concentrated.

This creates an uneven conservation landscape. Sharks may benefit from bans, sanctuaries, or improved enforcement, while rays continue to decline quietly alongside them. In some areas, divers still report regular shark sightings — but note that rays, once common, are now rarely seen.

That absence is easy to overlook because it’s subtle. Rays don’t aggregate dramatically in the same way sharks do, and their disappearance doesn’t always feel sudden. But ecologically, the loss is just as significant.

Protecting sharks has been an important step forward. Protecting rays requires recognising that shared ancestry doesn’t guarantee shared outcomes — and that conservation success for one group doesn’t automatically extend to the other.

🤿 How Diver Behaviour Affects Rays

Most diver impact on rays is unintentional. Very few divers set out to disturb marine life, and most interactions happen in moments of excitement, curiosity, or simple unawareness. But in popular dive regions, those moments add up.

Approaching cleaning stations too closely is one of the most common issues. When mantas or mobulas feel crowded or boxed in, they may abandon a station entirely. That doesn’t just end a photo opportunity — it interrupts parasite removal and forces rays to spend additional energy searching for alternative sites.

📍 Cleaning stations are essential, not optional

🚶♂️ Crowd pressure changes behaviour

🔁 Repeated disturbance compounds quickly

Chasing rays for photographs has a similar effect. Even slow, well-intentioned pursuit increases stress and energy use, particularly for animals that rely on efficient movement to conserve calories. Rays that are repeatedly followed learn to avoid certain areas altogether.

Hovering too low over sandy bottoms creates problems for bottom-dwelling rays. Stingrays and other benthic species are repeatedly flushed from resting or feeding positions when divers descend carelessly or maintain poor buoyancy. Over time, this disrupts normal behaviour and can cause rays to abandon otherwise suitable habitat.

🌫️ Fin kicks stir sediment

🐠 Reduced visibility alters feeding

🏝️ Shallow sites receive constant pressure

Sediment clouds created by poor buoyancy don’t just affect the moment. Fine particles can linger in the water, reducing visibility and interfering with feeding and navigation. In channels and passes, divers who surround or block moving rays can unintentionally cut off natural travel routes.

None of this requires malice, recklessness, or bad intentions. It’s the cumulative effect of small actions — hovering a little too close, staying a little too long, following just a few fin kicks more — repeated many times, by many divers, in the same places.

For rays, impact isn’t defined by a single encounter. It’s shaped by patterns. And those patterns are something divers have far more control over than they often realise.

🧭 How to Dive With Rays Responsibly

Responsible ray encounters are built on the same principles as reef-safe diving: control, awareness, and patience. Rays don’t need divers to manage or interact with them — they need space to behave naturally.

At cleaning stations, give mantas and mobulas plenty of room and remain low-impact and still. Position yourself well away from the station, maintain neutral buoyancy, and avoid drifting into the water column where rays approach. If a ray turns away, take it as a signal — not an invitation to move closer.

📍 Keep distance at cleaning stations

🫧 Stay neutral and still

⏳ Let encounters unfold naturally

Over sandy bottoms, buoyancy becomes even more important. Avoid hovering directly above resting stingrays or descending carelessly into sediment. A few poorly controlled fin kicks can flush rays repeatedly, disrupting feeding and rest. Maintaining height, trim, and awareness of what’s beneath you prevents most disturbance before it happens.

🌫️ Minimise sediment

🐠 Avoid repeated flushing

🏝️ Be especially cautious in shallow areas

Never chase, corner, or try to reposition a ray for a better view or photo. Rays that feel pressured will expend energy unnecessarily or abandon the area altogether. If a ray chooses to approach you, remain calm and still — don’t advance to meet it.

Just as importantly, manage your equipment. Secure gauges, hoses, and camera rigs so nothing trails below you. In tight spaces or sandy environments, dangling gear can cause disturbance even when your body position feels controlled.

The best ray encounters are often the quietest ones. When divers slow down, hold position, and let rays lead, interactions last longer, behaviour remains natural, and the experience is better for everyone involved.

Responsible diving with rays isn’t about rules or restrictions. It’s about recognising that doing less often allows you to see more.

🌊 Why Rays Matter to the Ocean

Rays are not just visually striking animals — they play important, often overlooked roles in marine ecosystems. Through their feeding habits, movement patterns, and interactions with other species, rays help shape how reef and coastal systems function.

🐚 Prey regulation

Many rays feed on animals living in or beneath sand and sediment. By foraging this way, they influence prey populations and help prevent any single group from dominating the seafloor.

🌊 Nutrient movement

As rays move between habitats — sand flats, reefs, channels, and open water — they help redistribute nutrients across ecosystems. This subtle movement supports productivity beyond the places where they feed.

📊 Indicators of balance

Because rays are slow to reproduce and sensitive to pressure, their presence often reflects long-term conditions rather than short-term change. Seeing rays regularly usually indicates that fishing pressure, habitat disturbance, and tourism impacts are being managed — even if not eliminated entirely.

When rays disappear, the effects tend to ripple outward rather than announce themselves dramatically. Early changes may be subtle: altered prey behaviour, shifts in sediment communities, or the quiet absence of species that once felt familiar. Over time, these changes can reshape reef and coastal dynamics in ways that are difficult — or impossible — to reverse.

This is why rays matter beyond the moment of encounter. They’re part of the background structure that keeps systems functioning smoothly. Their continued presence suggests resilience, balance, and space for wildlife to behave naturally.

For divers, seeing rays isn’t just a privilege — it’s often a signal that something is still working beneath the surface.

🧾 Final Thoughts: Rays Deserve More Than a Passing Glance

Rays are not background animals. They are slow-growing, highly vulnerable to cumulative pressure, and deeply affected by how humans use the ocean — yet they remain remarkably resilient when given space, time, and restraint.

Southeast Asia is still one of the best regions in the world to encounter rays in the wild. From mantas returning to the same cleaning stations year after year, to eagle rays crossing channels at speed, to stingrays resting quietly on sand, these encounters are still possible — but they are not guaranteed.

Whether that remains true depends less on admiration and more on behaviour. How closely people approach, how crowded sites become, how carefully divers move through sand and reef environments, and how pressure is distributed over time all shape what survives beneath the surface.

For divers, rays offer a quiet reminder. Some of the ocean’s most extraordinary animals don’t demand attention, chase interaction, or perform for an audience. They simply require respect — and the space to live on their own terms.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions About Rays

Are rays dangerous to divers?

Most rays are not dangerous and will actively avoid contact. Injuries usually occur when rays are accidentally stepped on or cornered. With good buoyancy and awareness, risk is extremely low.

Why do stingrays bury themselves in sand?

Burying provides camouflage, helps regulate body temperature, and allows stingrays to ambush prey hidden beneath the sediment.

Can rays feel pain?

Rays have complex nervous systems and respond clearly to injury and stress, indicating the capacity to feel pain and discomfort.

Why are manta rays declining in some areas?

Slow reproduction, targeted fishing, bycatch, and repeated disturbance at key aggregation sites all contribute. Even small increases in mortality can have long-term effects.

Are rays protected in Southeast Asia?

Protection varies widely by country and by species. While some rays receive limited protection, many remain poorly protected or entirely unprotected across much of the region.